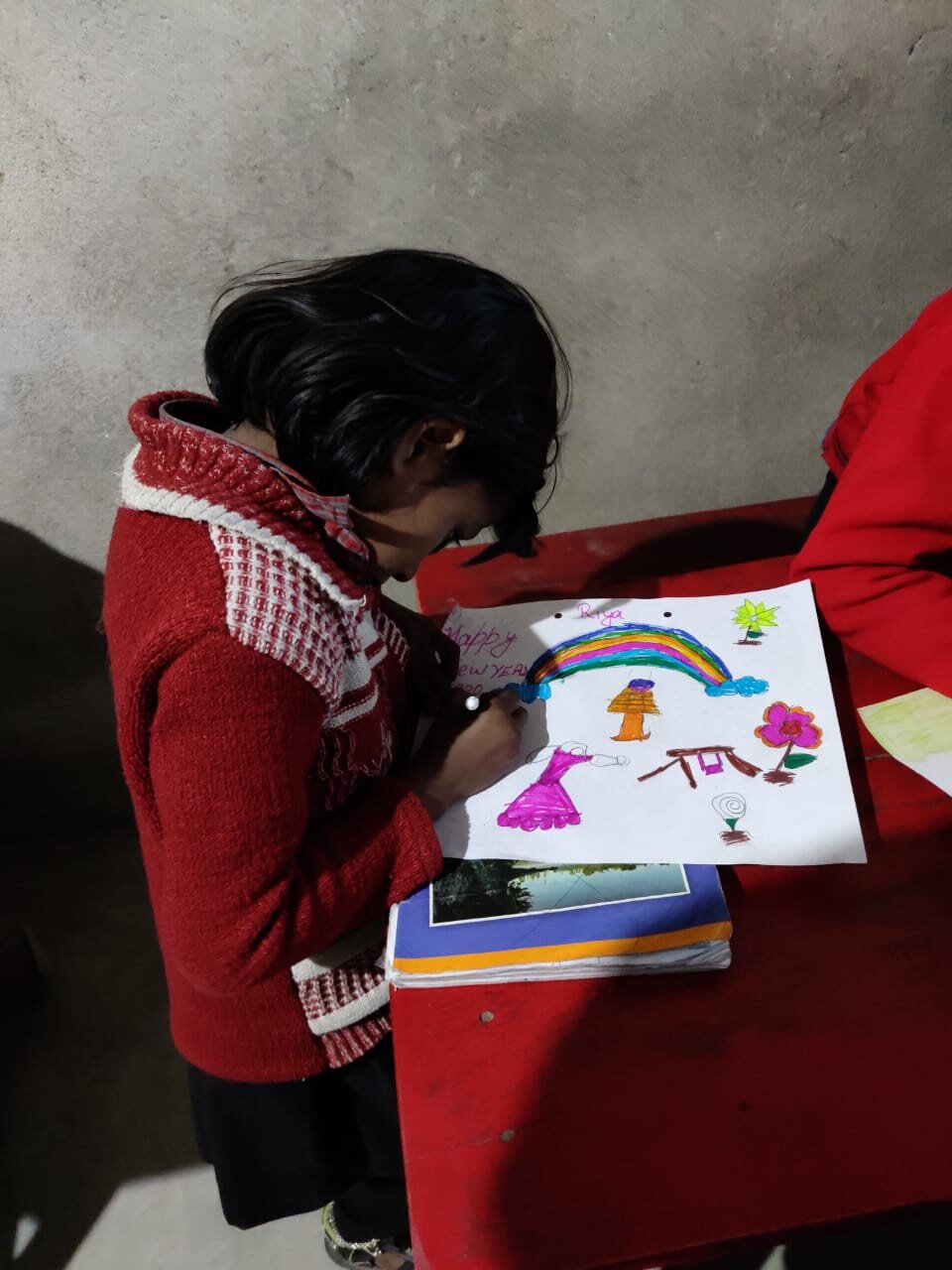

Inspiring a learning culture in rural India.

Tucked away in North-Eastern India’s impoverished Bakraur region sits Gautama Buddha Free School which provides free education to children aged 4-12. Driven by a commitment to provide quality education free from caste-based discrimination, founder Naresh Raj launched Gautama in 2005. But the idea, he says, goes back much further. “It was in my mind from a very young age. When I was in primary education I thought that, once I pass high school, absolutely I will do something for these people.”

Naresh has realised his vision with families in Sujata village, offering learning in blocks of just a couple of hours each, allowing children to continue supporting their families and helping at home during parents’ working hours. “We offer tutors, not a whole day of school. These children come from very poor families. They have to look after the younger children so their families can work. If I call them for a full day of school, they won’t come because they can’t be there for 6 or 8 hours. These are the hours the families need them to help support work.”

He hopes that Gautama can fill some of the well-documented gaps left by India’s government schools, not only around caste-based discrimination, but also regarding the quality of of education, generally. “There might be one out of five government teachers that are actually good,” he says. But he recognises that his work can improve outcomes in traditional education as well. “You can send your child to our place for two hours and they can study here. If you have time and your child has time, send that child to the government school as well. Anything they learn there, they can come back to our place after and expand upon.”

Gautama’s approach to education is holistic, Naresh says. “We want to teach them how to be.” Creativity is encouraged and students learn how to be honourable and respectful to their elders. Naresh also works with families to help them interact successfully with their children and get the best out of them. “I want to give the children and their families a passion for learning. I want them to learn from their parents’ work. If they are farmers, the children can learn practical skills from that to do better in life. You don’t have to be an engineer to be a good person.”

With Naresh’s naturally positive and gracious nature, it’s easy to think his journey has been straight-forward but, in reality, he has weathered numerous setbacks. In its earliest form, Gautama consisted of just Naresh and two friends teaching 10-20 children in an abandoned hospital building from which they were eventually evicted by the government. To this day, the hospital still sits abandoned. From there he set up shop in a community building in a nearby village but eventually got push-back from the community who wanted greater access to the space for other activities. Then it was a rental property to which the owners returned unexpectedly.

A few years ago he set up a vocational training programme for young women and girls to teach them sewing. “Women have to be at home taking care of the children, so they have more time. We wanted to help them use that time to innovate and earn some money. Empowering women is the best thing you can do to help a family,” he says. But then all of the sewing equipment got stolen and the initiative was shut down. Up until COVID-19 closed all education establishments back in March, Naresh was operating out of another rental which didn’t have have enough space for both the school and the vocational programme.

Like much of the world, Naresh is in a holding pattern until the pandemic begins to subside. Educational gatherings have been suspended for all children below the age of 14, with no announcement on when and how they might resume. Like all primary schools, Gautama will need government support and protective equipment before they are allowed to reopen.

“People are not living their lives any more. They are struggling just to survive their lives,” Naresh says. But he remains introspective. “It is so bad in the slums where no one has work. I hope that maybe those who are more lucky will see this and might give up their ego from their heart and be grateful for what they have.”

The government is trying to help with food – 5kg of rice and wheat per family each month – but it is not enough. Access to food and freshwater is poor and government initiatives are insufficient for countryside areas. Starvation is rife but with a recent contribution from Seed the Change| He Kākano Hāpai, Naresh has been able to help feed 20 local families. While he is eager to get back to his teaching work, Naresh understands that food and food security are the most urgent needs in the village. He continues to donate his own resources and time, with support from Seed the Change, to help his students and their families weather the pandemic storm.

As he looks to the future, Naresh is eager to build a school so that he can increase parents’ confidence and Gautama's credibility. His vision is to offer Gautama’s services to as many children as possible; to franchise in other villages where educational support is needed most and to bring more benefit to more children.

Seed the Change is gratefully accepting donations via The Gift Trust on behalf of Gautama Buddha Free School.